Light, health, sleep, and the buildings you live in

The Light Therapeutic – article on current research into the effects of light on health, with far-reaching implications for the design of buildings and cities, especially healing environments.

What is most startling is the way our bodies respond to light. Gloomy winter days are known to trigger a form of depression—seasonal affective disorder—which can be reversed if the sufferer sits by a large lightbox every morning. But light eases other forms of depression too: an Italian study found that bipolar patients in east-facing hospital rooms stayed nearly four days fewer than those in west-facing ones. Even physical conditions respond to doses of daylight: people recuperating from spinal and cervical surgery in bright rooms took fewer painkillers every hour; in sunny Alberta in Canada female heart-attack patients treated in an intensive-care unit recovered faster if they were exposed to lots of natural light. Mortality in both sexes is consistently higher in dull rooms.

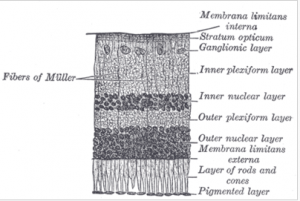

Much of what we’re learning now is about how the body receives and processes light, and how people respond to different light conditions. We’ve known, for instance, that our eyes have photoreceptors that have nothing to do with vision. The existence of these cells was postulated in 1923 and they’re mentioned in John N. Ott‘s 1973 Health and Light: The Effects of Natural and Artificial Light on Man and Other Living Things. Now we have a better understanding of the mechanics of this system.

One researcher studying that process is Satchin Panda at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences. He’s particularly concerned with the increased use of artificial light changing our sleep patterns, and the serious health consequences of disrupted sleep.

The eye perceives three main colours in light: red, green and blue, each vibrating at a different wavelength. In the morning, high concentrations of blue occur naturally; by dusk we are left mostly with green and red. The blue light has the greatest impact on our circadian system, telling the brain that it’s morning and time to be alert, and setting our clock for the day.

The problem is that artificial light does not replicate the colours of the natural world. Much electric light has high intensities of blue, so it deceives our brains into thinking that it’s daytime even when it isn’t. Just ten minutes of regular electric light can make some changes to our internal clock. “We evolved to be blue-sensitive, we need it,” says Panda. But many of us get an awful lot of it, particularly in the evening: when we get home we spotlight the kitchen so we can make the dinner, and then plug into our laptops, tablets or smartphones, which beam blue light into our eyes at close range. So we bombard our internal clock with mixed messages: our gloomy morning sends a weak signal to be alert; our over-bright evening shouts at our brain to rise and shine. We also lessen the contrast between light and dark that our circadian system relies on to work well. All of which makes us more prone to insomnia or disturbed sleep in some way.

An opthalmology professor in Japan, Kazuo Tsubota, says eyes are not only cameras that see, but also clocks that regulate our body’s circadian rhythm. He helped develop computer glasses that filter excessive blue light and convened a meeting of scientists, architects, and engineers to discuss improving the built environment’s effect on our health.

Last summer an international group of scientists (including Panda), doctors, ophthalmologists, architects and engineers gathered in Tokyo, all animated by the same question: how light affects health. That first meeting of the Blue Light Society was convened by Kazuo Tsubota, professor of ophthalmology at Keio University School of Medicine in Japan. After years of research, he had concluded that only if different disciplines collaborate can we adjust the way we live to the needs of the circadian system.

Architect Mariana Figueiro at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has been developing a lighting system for older adults that takes into account their increased need for proper light.

We are bad at judging how much light we get, says Figueiro, … “Our visual system fools us a lot.” We need more light to synchronise the circadian system than we do to see. …

Daylight is not intrinsically better for us than electric light, Figueiro says. It’s just that getting artificial light to do the same job “is more expensive, uses more energy and is more difficult to get right”. … Sleep disturbances magnify as we age: anything from 40% to 70% of people over 65 have serious problems dropping off, wake up often at night or struggle to keep their eyes open by day. Disrupted sleep often accompanies a general decline in our physical condition and immunity, as well as depression and other ills. Most of us assume this is just part of getting old. Not Figueiro. She reckons more exposure to bright light by day could help keep the doctor away.

She has created a lighting system specially for residential homes. If elderly people get two hours of morning sun every day for two weeks, their sleep improves; some research shows benefits even sooner. Yet most people see a fraction of that: one study found that middle-aged adults get about an hour of bright light a day, older adults in assisted-living facilities about half that, and those in nursing homes only two minutes.

There’s still much to learn about light’s impact on health and how buildings play into that crucial interaction.

In America, the advisory committee that sets the light standard for architects focuses on having just enough illumination to perform a task, says Frederick Marks, a Los Angeles architect: “People do not think about health.” He is a founding member of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, a group of scientists and architects looking at how buildings affect our behaviour and well-being.

You can see an excellent formal discussion between Satchin Panda and Frederick Marks in one of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture’s Interface lectures, a series that pairs a neuroscience with an architect to explore a specific topic. This lecture (1 hour and 16 min) is Circadian Regulation and the Light / Dark Cycle: How does Building Design Affect the Outcome? If you have limited time, try going 55 minutes into the clip where both speakers talk about the future and about light in specific architectural spaces.

Source for the image of Philip Johnson’s Glass House, here.

P.S. If you work on your computer at night, check out f.lux. It’s software that adjusts the color of your computer screen to that of the lighting in your environment, filtering out excessive blue.